Finding My Artist, Unlearning a Family Fact

It’s not your fault, Dad. Not in the way it would’ve been hers.

If Kim had said it, it would’ve been delivered sharply, meant to steer me back toward whatever version of myself she could tolerate. Your words weren’t like hers, they weren’t used as weapons. I know it drove her crazy to watch you be held in our affection, in your absence, in your flaws, in all the ways she could never live up.

More likely it was said as part of the deprecatory rigmarole, the modest little routine you do after someone offers praise, or when you point out somebody else’s brilliance, simultaneously exempting yourself from the category.

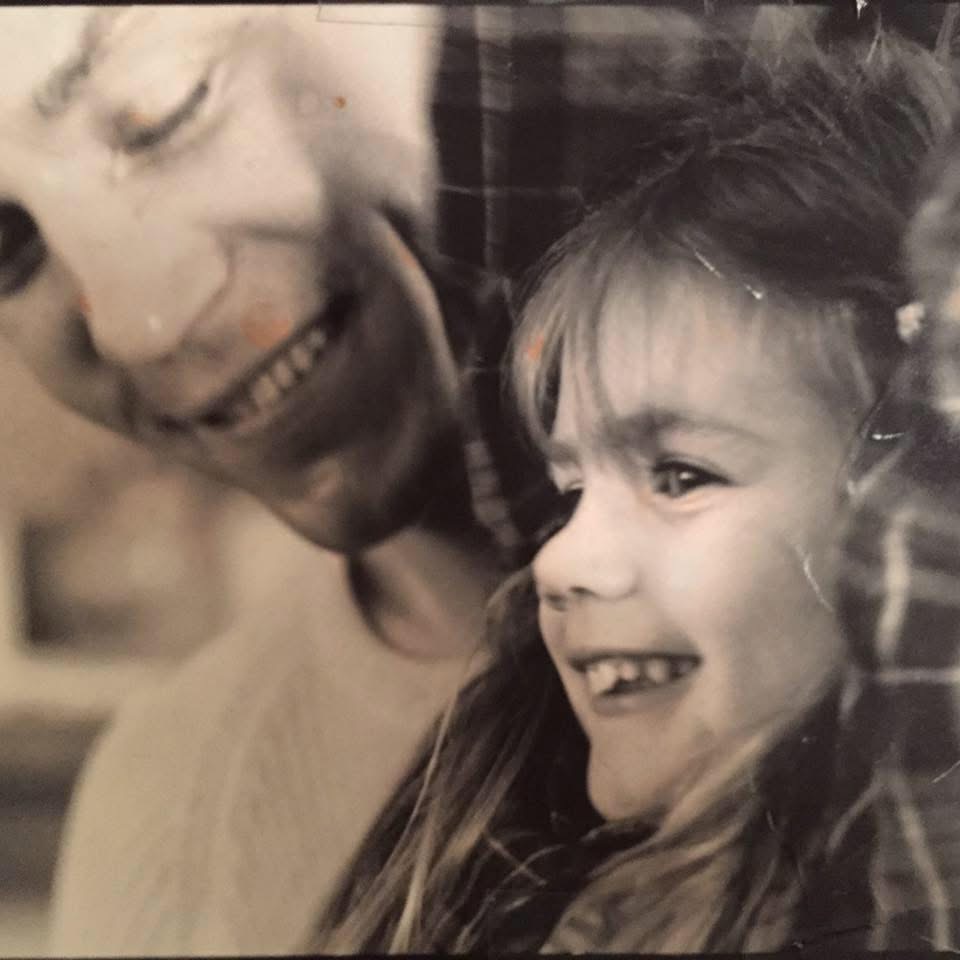

I was about seven, and the childhood spell of parental omniscience hadn’t worn off enough for me to question you. Alas, the Zellmans are deep, not quick thinkers, a trait I can now, after forty-one years safely trace back to you. You said it with oracular certainty, the casualness of it making it dangerous, sliding in like a harmless fact. And that was the problem, kids don’t know the difference.

“I’m sorry you’ve got the Zellman genes. We are not creative or smart.”

I’d be lying if I said I don’t still wonder who I might have been if that idea hadn’t been pressed into me while I was still forming. Back when my brain was soft clay, I absorbed whatever you said the way kids do, becoming household scripture.

I wonder if you thought you were doing me a favor, protecting me from disappointment. Offering your firstborn a smaller version of possibility so I wouldn’t reach too high and fall too hard. I can see how that could feel like love, especially if that’s what you were given, too.

It was also the 90s, a simpler time. Back when we rode our bikes without tracking devices and goldfish and cheese sticks qualified as health food. We didn’t have the internet to contextualize the things grown-ups just said and there was less of that “let’s unpack that” language. We didn’t spend time deconstructing every word wondering if they’d cause permanent damage. We just swallowed the story they put in our mouths as truth.

Which brings me to the name. You wanted to call me Skye Blu.

Names are rarely just names, they’re a first draft of identity, a label we wear before we can even speak, teaching us what kind of space we’re allowed to take up.

Recently, you told me a name like Skye Blu would’ve ruined me, because I wanted so desperately to fit in. And you’re not wrong that I wanted to fit in, perhaps just a misdiagnosis for the reason.

I didn’t want to fit in because I was naturally bland. I wanted to fit in because it felt safer than standing out, and there were no rewards for standing out in our house. So, I got strategic, studying other people’s lives like they’re instruction manuals, trading tuna on wheat for peanut butter and fluff even though I always knew it was disgusting. Pretending to love Nintendo when I’d rather have read a book. I picked “normal” out of desperation, searching for safety.

So sometimes I wonder, what if I had been Skye Blu?

What if I’d been given a name that insisted on uniqueness? What if my own name had been a daily reminder that I was allowed to be different, bright, strange, and still safe? Would that have changed your messaging to me, too?

Could you have found language for the kind of love like Mr. Rogers offered? An uncomplicated safe place where a grown man looked right at us and said, “There’s no person in the whole world like you, and I like you just the way you are.” I don’t think you had those words, Dad, not then, maybe not ever, but sometimes I wonder what might have been different if you did.

Maybe you were just passing down what your father handed you, the same limited language, the same “be realistic” love, because that’s what you knew.

But let’s be honest, Skye Blu probably wasn’t going to survive Kim’s mouth.

Kim would’ve tried to make a name like that behave – edit it down, correct it mid-sentence, sand it smooth until it stopped drawing attention. Skye Blu would’ve become a battleground of a different kind. So I became Danielle Nicole: a name that could blend, that could get good grades, that didn’t require anyone to explain me.

And still, she held me back, trimming my creativity down to something she could control. Fear and shame were the universal language in our house, leaving no room for Skye Blu or Danielle Nicole. So no, it couldn’t be the name that was risky. It was me.

I’m not blaming a name for my limitations, I know better than that. I”m saying our identity gets shaped by the messaging around us, the stories our parents repeat. By what they praise, what they shut down. By what feels safe and what doesn’t.

Kids don’t just hear those messages; they metabolize them, stack them like bricks, and build a private narrator out of whatever they’re given, carrying it for decades until one day, if they’re lucky, they get brave enough to ask the question that changes everything:

Who am I, underneath what I was told?

So I’m here to tell you, Dad:

the Zellmans are indeed wildly creative and smart. And whether you meant to or not, you’re part of the evidence.

And I know this might not be your truth anymore. I know you might not even recognize yourself in the version of you I’m describing. After all, you’re the one who shared your gift of words and writing with me. I treasure those brief entrances into your mind. A man of few words… until you get talking.

And then you become an artist of them.

Which is why I keep circling back to the same question:

If we weren’t creative, Dad,

what have we been doing all this time?